The Disease

The incubation time (the time from exposure to first symptoms)

usually ranges from 1-6 days, although cutaneous cases have

been reported as long as 60 days after exposure.

There are three major anthrax syndromes in humans

- Cutaneous anthrax

- Inhalational anthrax

- Gastrointestinal anthrax

Cutaneous anthrax

When anthrax spores are introduced into the body through a

break in the skin, they multiply and spread locally. The release

of three toxins - edema factor, lethal factor and protective

antigen - leads to tissue swelling and necrosis (cell and

tissue death).

Three to five days after exposure, a small, painless, itchy

bump develops in the exposed area (usually face, neck, arms,

hands). The lesion then develops into a vesicle and finally

an ulcer with a characteristic black centre. There is often

significant swelling associated with the skin lesion. Left

untreated, and small but significant proportion of cases may

progress to systemic infection and even death. Treatment with

antibiotics, however, is very effective in preventing systemic

illness.

|

Cutaneous Anthrax Infection of the Hand

and Cheek

Photos taken from the New England Journal of Medicine.

Panel A shows the characteristic blackened eschar

surrounded by eroded areas and massive edema. These

lesions are painless. The areas of "dried skin" represent

resolving edema. Lesions continue to progress despite

rigorous antibiotic treatment. Cutaneous anthrax

can be self-limiting, and the lesions resolve without

scarring. About 10 percent of untreated cutaneous

anthrax infections progress to systemic

anthrax. Panels B, C, and D show

changes in the lesion on the cheek over a seven-day

period. The characteristic blackened eschar is present

on day 0 (Panel B). Facial edema and ulceration occur

by the second day (Panel C). On day 7, the lesion

is beginning to heal, and the facial edema is resolving

(Panel D). |

Inhalational anthrax

Anthrax spores inhaled into the lungs are taken to regional

lymph nodes in the chest. Multiplication of the organism leads

to inflammation and destruction of these lymph nodes and spread

into the bloodstream.

Early diagnosis of inhalation anthrax is difficult, as the

initial symptoms are non-specific and flu-like (fever, muscle

ache). However, these symptoms rapidly progress two to three

days later, with the development of low blood pressure (shock)

and respiratory problems such as shortness of breath. At this

point, the disease is usually fatal even if antibiotic therapy

is started.

Gastrointestinal anthrax

Gastointestinal anthrax is extremely rare. It most often occurs

as multiple cases in households following the consumption

of contaminated meat. Microscopic examination of intestinal

tissue reveals inflammatory infiltrates, ulceration and swelling

similar to that of cutaneous anthrax. Symptoms are variable

and include fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea

and the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity. Death

occurs from intestinal perforation or shock from fluid imbalances.

Reported mortality rates range from 25% to 75%.

|

|

B. anthracis is a large, nonmotile, gram-positive

aerobic rod capable of forming spores. It is a member of a

group of bacilli that are encountered in the laboratory as

a normal skin contaminant. B. anthracis can be differentiated

from the other bacilli in this group morphologically and through

biochemical testing.

Anthrax is diagnosed by isolating B. anthracis from

skin lesions, sputum, abdominal fluid or feces depending on

the suspected anthrax syndrome. The organism is almost always

found in the blood. Detection of anthrax antibodies in the

blood is also possible.

|

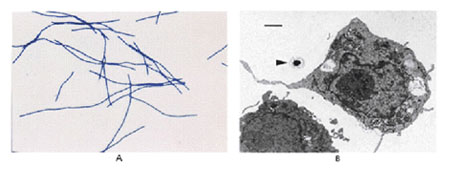

Photomicrographs of Bacillus

anthracis Vegetative Cells and Spores

Photos taken from the New England Journal of Medicine

Panel A shows a Gram's stain of B. anthracis

vegetative bacteria. The bacterial cells exhibit gram-positive

staining (purple filaments) (x600). Panel B shows an

electron photomicrograph of a B. anthracis

spore (arrowhead) partially surrounded by the pseudopod

of a cultured macrophage (x137,000). The bar represents

1 µm. |

B. anthracis can be treated by a variety of antibiotics.

Penicillin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, erythromycin, streptomycin

or ciprofloxacin can be used. As many of the symptoms of anthrax

are mediated by toxin release, the role of antitoxins in the

management of inhalational anthrax infection is under investigation.

However, there are no preparations currently available. Antibiotic

administration to asymptomatic patients after an exposure

to anthrax is also recommended.

|